by Greg Walcher, E&E Legal Senior Policy Fellow

As appearing in the Daily Sentinel

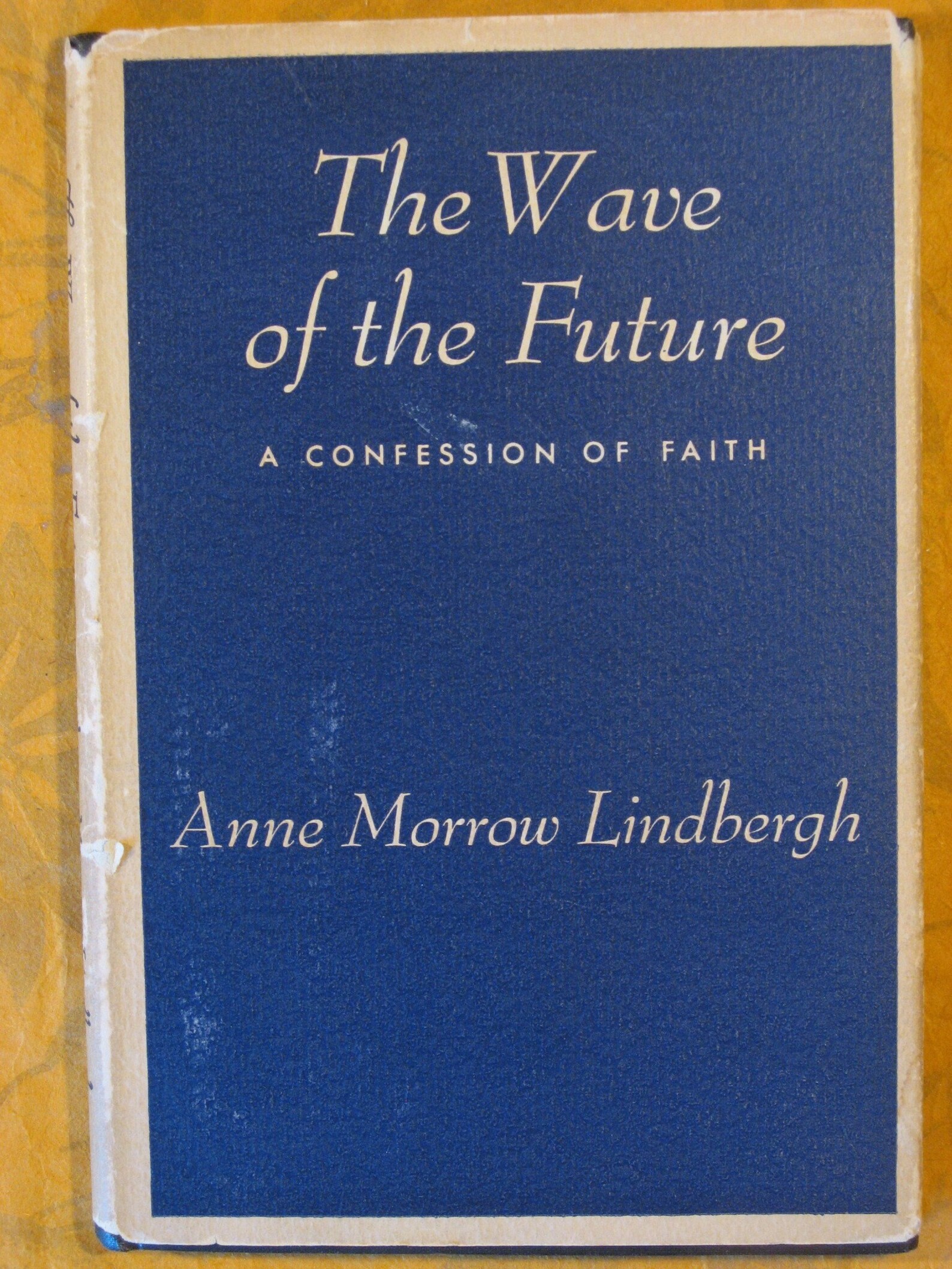

The Dutch electronic band Quadrophonia had a minor hit in the 1980s called “Wave of the Future” — hardly an original title. It was the name of Anne Morrow Lindbergh’s 1940 book calling for appeasement with Hitler. Various magazines predicted that the “wave of the future” would be nuclear powered vacuum cleaners, flying cars, shopping malls, and ad-free television. Fascism was called the “wave of the future” by some 1930s academics. My favorite is a scholarly study that calls city-states — the staple of the ancient world — the “wave of the future.” 1940s Interior Secretary Harold Ickes famously said, “The so-called wave of the future is but the slimy backwash of the past.”

City planners and politicians continue to call mass transit the wave of the future, despite Americans’ continually declining use of ever more subsidized transit systems. Most of our lives, planners have been in love with light rail, high speed trains, and intercity buses — all century-old technologies. The first “bullet train” was not built by Japan in the 1960s, but by the New York Central Railroad in the 1930s. It was discarded by the 1950s as modern Americans abandoned trains in favor of cars and planes.

They still prefer their cars, and governments cannot change that, though they spend over $80 billion annually trying. The Biden administration just allocated another $3 billion to California’s high speed rail fiasco, known by critics as the “train to nowhere.” That’s a sad comment considering the exciting initial promise. It started as a 2008 ballot initiative asking voters to approve $10 billion in bonds for a Los Angeles to San Francisco bullet train, to be completed by 2020. It sounded like a good idea to many, though it barely passed amid concerns that the price tag might grow. Ya think?

Before the end of the first year the cost had tripled. Then the route was changed to utilize existing tracks for large portions, so it is no longer considered “high-speed,” and it doesn’t go to either Los Angeles or San Francisco. If you want a slow train from Merced to Bakersfield you might be in luck, though the projected cost is now well over $100 billion, not primarily financed by voter-approved bonds but by the rest of the nation’s taxpayers.